How Recent Policy Shifts Are Reshaping Australia’s Immigration | Australia Immigration News

Australia's recent cabinet reshuffle signals shifts in immigration policy, reflecting public concerns and historical immigration trends. Explore the impacts and future implications of Australia's immigration policy changes.

The recent cabinet reshuffle by the Albanese government suggests a shift in its stance on immigration. The removal of Andrew Giles from his role as immigration minister, assigning him to the Skills and Training portfolio (now a part of the outer ministry), alongside Home Affairs Minister Clare O’Neil being reassigned to Housing, signals a potential political response to the growing concerns surrounding immigration.

Giles’ demotion appears to be a consequence of the release of immigrants who were illegally detained, some of whom are convicted criminals, into the community. Public unease over the sustained high levels of immigration also contributed to his exit. Last year, O’Neil, then serving as the Home Affairs minister, pledged to drastically reduce Australia’s immigration intake, a promise that proved to be less ambitious in practice than in rhetoric, merely adjusting the inflated figures seen post-pandemic.

Their reshuffle comes despite recent attempts to cap international student numbers, efforts that were ultimately not enough to shield Giles and O’Neil from the political fallout. Instead of shifting blame onto his ministers, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese missed a key opportunity to address public anxieties by informing Australians about the historical patterns of immigration.

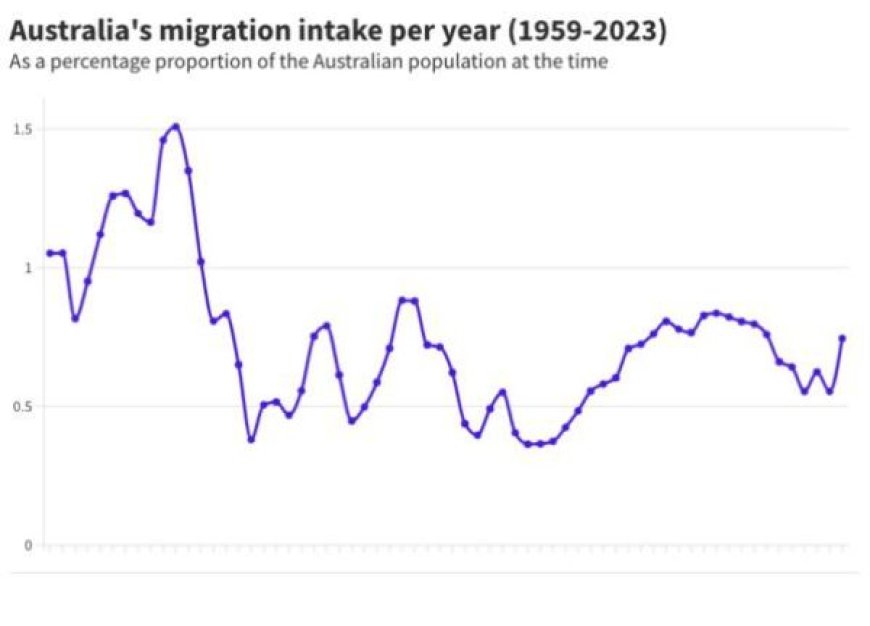

Looking at historical data, it's clear that Australia has experienced similar, if not greater, levels of immigration in the past. In fact, as a proportion of the population, Australia currently takes in about half the number of immigrants compared to its peak in the late 1960s.

A Historical Perspective

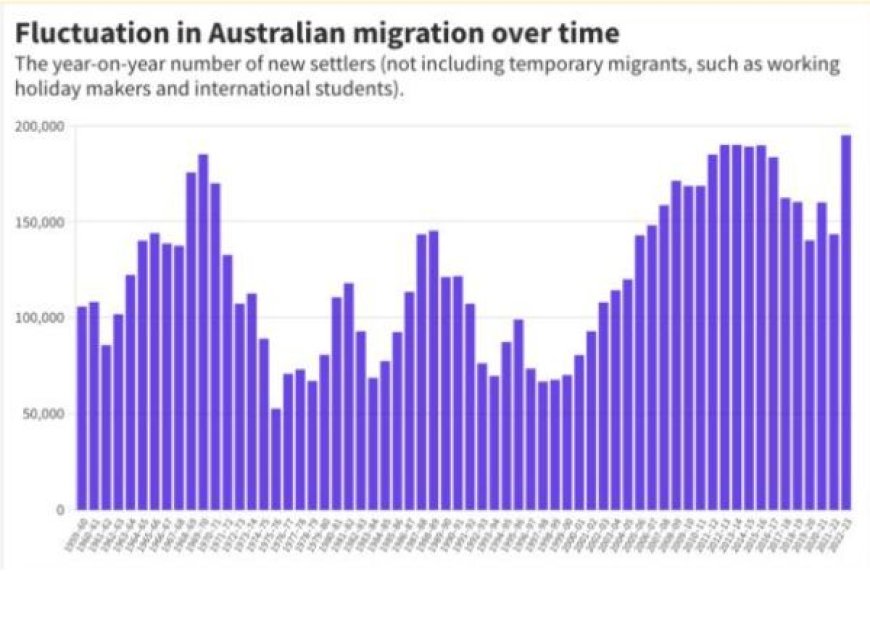

Australia's permanent migration program, as illustrated in Figure 1, shows the ebb and flow of migration levels from 1959/60 to 2022/23, largely in response to the nation’s economic conditions and political climate. This data excludes temporary migrants, such as working holidaymakers and international students, who either leave at the end of their visas or apply for permanent residency. Including temporary migrants in calculations of Australia’s ‘net overseas migration’ intake, which some media outlets claim exceeds 500,000, can be misleading and cause unnecessary alarm.

The post-World War II economic boom and the urgent need to increase the population drove a significant immigration program. Subsidized travel for Europeans, particularly Brits, under the ‘assisted passages’ scheme contributed to this influx.

However, by the 1970s, immigration levels dropped due to improved economic conditions in Europe, eliminating the main reason for emigration, and the policies of the Whitlam Government. Despite being lauded by the political left, Gough Whitlam's stance on immigration was complex. His government formally ended the White Australia policy but also reduced immigration to its lowest level since World War II, driven by the economic downturn following the 1973 oil crisis and traditional Labor fears that immigrants would take jobs from native-born workers.

Ups and Downs in Immigration

Under the Fraser Government (1975-83), immigration increased, particularly to accommodate the influx of nearly 60,000 Vietnamese refugees after the Vietnam War. However, this was short-lived, with numbers declining again during the early 1980s recession. The Hawke/Keating governments later opened Australia’s economy to the world, leading to a sharp rise in immigration during the 1980s. But this surge was tempered by the early 1990s recession.

The Howard Government, despite initially cutting immigration in response to rising anti-immigration sentiment, notably from Pauline Hanson, eventually oversaw a significant expansion of the program. This growth was only temporarily halted by the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-2009.

The immigration program continued to expand under the successive governments of Julia Gillard, Kevin Rudd, and Tony Abbott, demonstrating the resilience of the Australian economy. However, even before the COVID-19 pandemic, immigration numbers began to decline, partly due to Home Affairs Minister Peter Dutton (2017-21) tightening visa application scrutiny to weed out fraudulent claims.

Despite claims that these cuts were planned to ease urban congestion, the real reason for the decline in immigration was a higher-than-usual rejection rate, particularly for older applicants with complex health histories deemed too ‘high risk’ for admission.

This example from the late 2010s highlights how immigration is often used as a political tool to address unrelated social issues, such as inadequate urban planning.

A Long-Term View

Figure 2 shows the raw numbers of immigrant arrivals as a proportion of Australia’s population. With Australia’s population growing from 10 million in 1959 to 26 million in 2023, the overall trendline is downward. At its peak in the late 1960s, immigration accounted for 1.5% of Australia’s population. Since then, this figure has never exceeded 0.84%.

These figures suggest that concerns about being overwhelmed by immigrants are unfounded. When viewed in the context of the last 50 years, current immigration levels are well within historical norms, especially when considering Australia’s population growth.

What is new, however, is Australia’s increased reliance on temporary migration, including working holidaymakers, international students, and New Zealanders, who are exempt from visa requirements. Cutting immigration, whether permanent or temporary, would have serious consequences for Australia’s economy and society.

While politicians may find it tempting to use immigration as a solution to political problems, the long-term impacts on Australia’s economy, society, and international reputation could be significant and enduring.

Tags:

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0